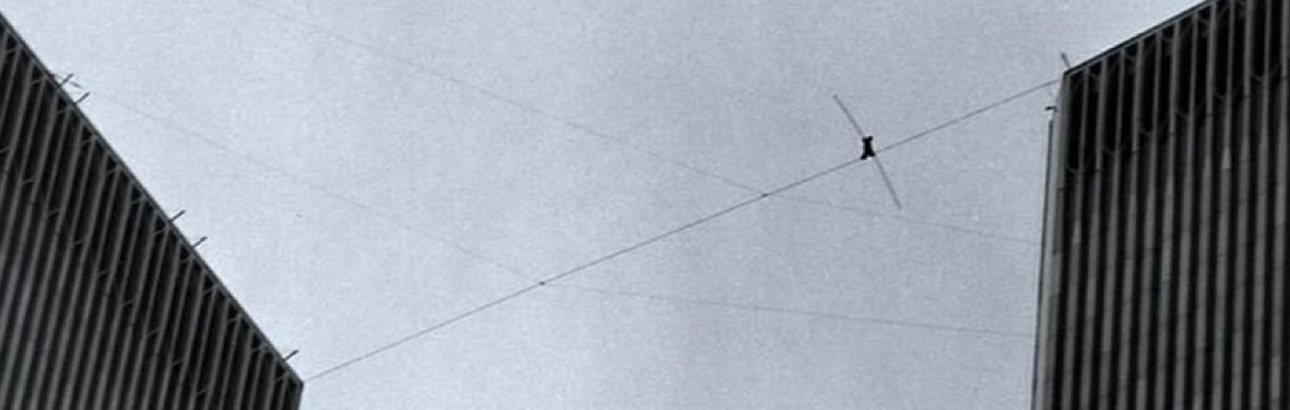

In 1974, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center complex stood as the highest buildings in the world. On the morning of August 7, Phillipe Petit, a 24-year-old Frenchman, stepped off the edge of the south tower to walk the wire he had rigged between them.

This was not an official stunt. In fact, Petit referred to it as his “le coup, the artistic crime of the century” and spent six years planning. It all led to roughly 45 minutes spent on the wire, where he made eight passes back and forth between the buildings — including kneeling and lying down on his back — before walking off the other side to the waiting handcuffs of police.

The entire story was captured by Petit and his crew and was later turned into a documentary called “Man on Wire,” in homage to the description from the original police report. “Man on Wire” was completed in 2008 and won several prestigious awards, including the Grand Jury Prize from the Sundance Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Documentary. The movie is terrific; I recommend you make an effort to see it.

I was reminded of Petit recently while watching a TED Talk he gave in March, ’12. As he described what it was like to take that first step from the edge of the building at the top of the world, I couldn’t help but think of how his words applied to every endeavor, every project, every effort we make.

Those of us who work at desks are not often faced with being on the edge, but there are certainly events that push us beyond our comfort zone and raise the blood pressure. Expectations, either internal or external, exert tremendous forces that must be dealt with in order to succeed. Here is how Petit describes these moments and how he quiets the “inner howl” that assails him. The words are his, the emphasis is mine:

On the top of the World Trade Center, my first step was… terrifying.

All of the sudden, the density of the air is no longer the same. Manhattan no longer spreads its’ infinity; the murmur of the city dissolves into a squall whose chill and power I no longer feel… I lift the balancing pole, I approach the edge, I step over the beam. I put my left foot on the cable. The weight of my body rests on my right leg, anchored to the flank of the building. I ever-so-slightly shift my weight to the left, my right leg will be unburdened, my foot will freely meet the wire.

An inner howl assails me: the wild longing to flee. But it is too late. The wire is ready. Decisively, my other foot sets itself onto the cable.

‘Faith’ is what replaces ‘doubt’ in my dictionary.

When he puts one foot on the wire, he has the faith — the certitude — that he will perform the last step. If not, he says, he would run away and hide.

You cannot have a project or goal if you don’t have faith. If not, it will be like ‘Oh, I hope, one day, you know, that success will fall from the sky and I’ll be there to receive it.’ It doesn’t work like that.

“There is no recipe, there is no algorithm, parameter or algebraic formula that I could give to say, “If you need to concentrate in duress or in an amazing moment in your life, do this or do that…” it all depends on who we are.

But I believe he has provided the formula: We have to know both where we’re starting and where we’re going, and we must have absolute faith that we’ll get there. If we do, taking that last step will be as certain as the first.